How Do We Prepare for Sea Level Rise With Equity in Mind?

Plus the Big Beautiful Bill's impact on California climate action and other important climate news.

Welcome to issue number 10 of State of Change, a project of the Climate Equity Reporting Project at Berkeley Journalism.

Climate News in California

Federal Action That Impacts California

All eyes are on the U.S. Senate as it hammers out its version of the “Big, Beautiful Bill.” So far, multiple outlets have reported that lawmakers are sticking fairly closely to the House’s version of the bill, which guts a range of programs built to support renewable energy production around the country. One of the biggest outstanding questions centers around the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tax credits for EVs, rooftop solar, and home electrification, which the House voted to do away with last month. Five Republican senators have pushed back against the cuts, but it’s not yet clear whether they will opt to vote against their party. And it could be another week or two before the Senate Finance Committee weighs in on the tax credits.

If they get cut, the tax credits could begin phasing down in 2028, and many projects could be forced to meet an end-of-year deadline to start construction. But in California — which requires strict environmental impact reporting and permitting requirements — launching new projects can take years. In other words, many projects will stop before they’ve had a chance to start.

The bill would most likely radically shrink the solar industry on a national scale. The Solar Energy Industries Association released a report this week that estimates as many as 300,000 jobs could be lost in the industry.Meanwhile, the Department of Energy also put forward a budget that would slash $3.7 billion in funding for carbon capture projects and other efforts to cut greenhouse emissions from power plants and industrial sites. It has also committed to overhauling the department by cutting spending for offices focused on renewable energy.

The Energy Transition

Donald Trump signed four executive orders last month aimed at fast-tracking the expansion of nuclear power production in an effort to meet the demand by tech companies to power artificial intelligence. Diablo Canyon, California’s only operating nuclear plant, was supposed to cease operations this year, but has been permitted to continue operating until 2030. PG&E has also a 20-year license extension, with hopes of staying upon until 2045. The state has a moratorium on new nuclear power plants, but in light of the recent deals Google and Meta have brokered with large nuclear providers outside California — and the push by many to see the new generation of small modular reactors as a safer, more benign option — industry groups pushing for a nuclear power “renaissance” in the state may have a new tailwind.

A bill that would direct 15 million tons of forest biomass to electric power facilities every year is moving through the legislature. And while the biomass wood pellet production is poised to expand in the state, many climate advocates see it as a false solution.

A geothermal project in Sonoma and Mendocino counties has positioned itself to nearly double the region’s local geothermal electricity output. Sonoma Clean Power plans to recruit 30% local residents and create 1,000 permanent jobs, although it is yet to pass legal, financial, and regulatory hurdles. Geysers in the region already power 725,000 homes, making it the world’s largest geothermal power complex. The project will also partner with Mendocino College and local high schools to grow its clean energy training programs. Students will be trained on solar, cleantech, HVAC, and sustainable construction. Geothermal jobs offer competitive wages and require many of the same skills needed to work in the oil and gas industry.

Building Electrification

Residents of Foothill Farms, a 138-unit affordable housing complex for older adults in Sacramento, are breathing cleaner air thanks to a major switch from gas to electric appliances. The owner of the complex made a slew of upgrades, including adding heat-pumps, electric vehicle charging stations, and 240-volt power outlets. And thanks to Sacramento’s municipal utility, electricity rates in the city are lower than most other parts of the state, making it a smart place to invest in larger-scale electrification projects; each unit could save over $200 per year, and the building’s owners could see annual savings of around $25,000 by replacing gas costs with electricity.

AB 39, also called the “Local Electrification Planning Act,” has advanced from the Senate Appropriations Committee and will now be put to a vote on the Senate floor, according to the Building Decarb Coalition. The bill will require California cities to prepare for building electrification by integrating it into their planning processes between 2027 and 2030. It stipulates, among other things, that all plans include “policies and implementation measures that address the needs of disadvantaged communities, low-income households, and small businesses for equitable and prioritized investments in zero-emission technologies that directly benefit these groups.”

Transportation

Another day, another legal battle. The United States Senate has voted to put a stop to California’s electric vehicle requirements, a move that Donald Trump has pledged to enact into law. In response, California, which sets its own vehicle emission rules, has indicated plans to sue. If the state prevails, starting next year, 35 percent of new vehicle sales in the state will consist of either zero-emission or plug-in hybrid vehicles, as part of efforts to improve the state's air quality.

Ava Community Energy, a community choice aggregator or CCA based in the Bay Area, has rolled out a new virtual power plant initiative to maximize the potential of renewable energy sources. The first program under this initiative encourages owners of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles to charge their cars during daylight hours so they can use clean energy, earning up to $100 in incentives and saving on their energy bills. Ava has set a goal to enroll 5,000 vehicles in the first year.

Agriculture

AB 947, a bill that would give farmers in California access to the Healthy Soils Program is also moving through the legislature. The bill would update the Cannella Environmental Farming Act of 1995, and require the California Department of Food and Agriculture “to establish and oversee a sustainable agriculture program to provide research, technical assistance, and incentive grants to promote agricultural practices that support climate resilience for farms and ranches and the well-being of ecosystems, air quality, and biodiversity.”

A recent study from the University of California Merced revealed that the Central Valley is home to roughly 77 percent of California's idle farmland and that land is linked to nearly 90 percent of human-caused dust events. Dust brings a range of health problems, particularly respiratory illnesses. While idle lands are not uncommon, the dust issues may be an unintended consequence of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which requires farmers to reduce their water usage. To address this issue, the researchers suggested using cover crops or ground cover to keep roots in the ground and reduce dust production.

The USDA has announced that it will disincentivize “the use of federal funding” for solar and will reconfigure its Rural Energy for America program or (REAP). Farmers only recently saw funding unfrozen, and now the program could be phased out entirely.

Housing

A contentious bill that would allow more apartments near public transit stations in California narrowly passed through the state Senate on Tuesday. Senators voted 21-13 to advance it to the Assembly. SB 79, which was initiated by Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, would permit the construction of buildings between four and nine stories close to certain high-frequency bus stops, trains, and ferries. The goal is to bolster housing construction, get more people out of cars, and buoy besieged public transit agencies still recovering from the pandemic, says Wiener.

Climate Impacts

Snow is literally having a meltdown. According to the National Integrated Drought Information System, the snowpack in the western United States is melting at a record-breaking pace, driven by high temperatures and low precipitation levels. Early peak runoff poses challenges to California's water management system, which was built around historical patterns. Beyond the concerns this raises around water availability, flooding, drought, wildfires, and agriculture, the East Bay Times says the absence of spring runoff reduces hydroelectric capacity — a vital power source for western states.

Sacramento county will likely face population decline in the coming decades due to flooding. Earlier this year, First Street, a well-known risk prediction firm, released a report predicting that the county could lose an estimated 28% of its population by 2055. The report also cited deteriorating air quality and demographic shifts as other drivers that will contribute to the decline. Sacramento is at a high risk because of its low elevation proximity to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The city faced extreme flooding in the 19th Century and scientists have predicted that another megastorm could hit the region in the coming years.

Governor Gavin Newsom has asked the legislators to speed-up the contentious $20 billion Delta Conveyance Project in hopes of seeing it completed by 2027. He asked the lawmakers to enact a trailer bill to truncate judicial reviews of lawsuits. The project includes a 45-mile-long tunnel to reroute water all over Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. If completed, it will move water from the Delta to the agricultural regions in the Central Valley — a shift that would be a boon for farmers but a major loss for ecosystems in Northern California. The project has been in place in many ways for about 50 years, sparking continuous opposition from Delta region lawmakers and environmental groups, who cite habitat demolition and lack of transparency.

A new analysis from UC Irvine found that the hot, dry, and windy weather that ignites wildfires is becoming more frequent across California and other parts of the western U.S. due to climate change. "Fire season" has spiraled into a yearlong phenomenon, draining fire departments and over-burdening others tasked with mitigating or stopping blazes. The average number of "fire weather" days per year increased by 37 in the Southwest and 21 in the West between 1973 and 2024, according to an analysis from Climate Central, a climate research group Wildfires have been spreading worse with each passing year this century, with a significant increase in “extreme” wildfires scorching more that 10,000 acres.

A little good news

California officials released thousands of gallons of water to create new wetlands along the shores of the shrinking Salton Sea. According to the Los Angeles Times, the Species Conservation Habitat Project is the biggest state attempt to solve environmental problems at the lake. The project’s goal is to control dust, provide a place for fish and birds, and cut down on toxic dust in the predominantly low-income Latino communities around the sea. In April, water was released to deluge ponds close to the lake’s south shore. And the first 2,000 acres of wetlands are now flooded. The project is envisioned to expand to 9,000+ acres with the support of $245 million in federal funds. The project is part of a 10-year state plan to construct 30,000 acres of wetlands and dust-control projects by 2028 — an effort that has so far fallen short.

For the first time in its 57-year history, Lake Oroville, California's second largest reservoir, is full for the third consecutive year. The lake is now 100% full, at its maximum level of 900 feet. Authorities are considering releasing some water in order to prevent flooding, but the overall conditions are positive for the state, as the reservoir provides water to 27 million residents and 750,000 acres of farmland.

The Q&A: How Can the Bay Area Plan For Sea-Level Rise?

By Cole Haddock

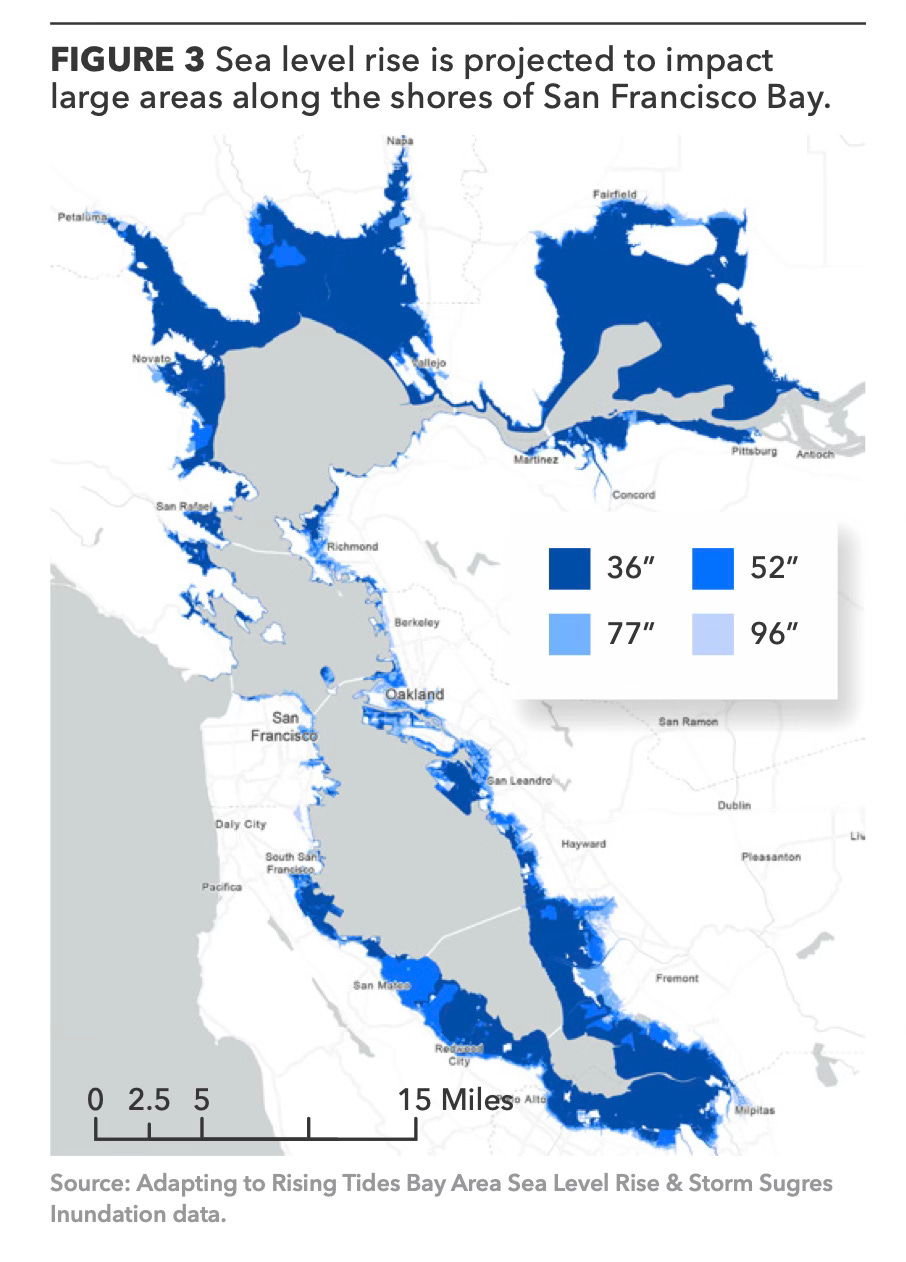

Bay Area communities are not sufficiently prepared for the sea-level rise and flooding that is predicted to occur in the decades ahead. The impending risk is massive; estimates range from two feet to as much as ten feet of sea-level rise by 2050. It’s a change that would submerge almost all of Foster City and large parts of East Palo Alto.

While mitigation is still possible, some form of sea-level rise and extreme flooding is inevitable. As Dr. Zachary Lamb sees it, it’s crucial that we begin to plan now, in order to protect the millions of people that live along the bayshore.

Lamb is an assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at U.C. Berkeley and the co-author of the recent report, Bayshore Urbanism: Property and Climate Change Adaptation on San Francisco Bay. In the report he and Robert Olshansky argue that in order to respond effectively and equitably to sea-level rise, we must rethink property ownership and advance creative collective action instead.

Trained classically as an architect at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lamb started working in climate resiliency and urban planning in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, one of the most devastating storms in American history. He says the consequences of flooding in Louisiana demonstrated that, “the infrastructures that had allowed our cities to grow and prosper over the course of the previous 200 years, were clearly less and less well-suited to the realities of a climate change impacted world.”

We spoke with Lamb about his research, the state’s new requirements for coastal cities, and the potential for big changes to the bay shoreline.

If you're a Bay Area property owner and you live in a place that you know is going to flood, what rights do you have, what protections do you have, and how does that vary from city to city?

There are ongoing debates in California right now about the rights of property owners who are trying to stop sea level rise from swallowing their property. There are legal cases in which you have private property holders who are living on rapidly eroding cliff edges. Those owners want to be able to reinforce those dune edges so that their houses don't drop into the ocean. But contrarily, institutions like the California Coastal Commission are increasingly telling folks, “You can't do that.” You can't stop sea level rise, because if each individual property owner takes actions to stop sea level rise from impacting their property, that tends to have negative externalities for other people around them.

But it’s also important to understand that with a lot of these kinds of emergent hazards and vulnerabilities, private property owners will lobby state and local county officials to invest in infrastructure to protect them. Generally speaking, wealthier, more empowered folks who own property have a louder voice, and tilt the balance towards supporting and protecting high value property.So people who live in more expensive places and more expensive homes tend to get more than their share of public investment to protect their assets.

I think it's interesting that we're living in a world now where our maps of where land begins and ends are not really true anymore.

If my grandma’s house is right in the flood zone, she would have no guaranteed right to assistance or compensation from the state?

She can certainly sell. But the amount of public resources available from the entities who would do that buying out is inadequate given the scale of this problem. There's lots of different ways that municipalities have thought through how to do buyouts in ways that would be both fiscally responsible and just. There was some state legislation proposed a couple years ago that would have offered voluntary buyouts to people if they lived in certain zones. You could have gotten a voluntary buyout, and then the State would rent your house back to you.

In the report, we talk about the idea of rolling easements, which is another strategy that has been explored in various places. A governmental, or in some cases, a non-governmental entity, could buy an easement, then they could gradually take over a property as sea level rise hits different physical benchmarks. That's a way that people could get a bit of a buyout, but still have time to be in their place until they can't be there anymore.

Can you please explain the role of the San Francisco Bay Conservation & Development Commission (BCDC) and the impact that SB 272 has had on the Bay Area? How successful has that project been? How much power do they actually have? Do you think there should be a more regional response or more power given to the BCDC?

The fact that we have the BCDC means that the Bay Area is actually better situated to confront these questions than a lot of other places. For a process like sea level rise, which is global in scope, there’s a lot of adaptation that you cannot do as an individual city. There’s a need for regional coordination. Partially so that lower-resource municipalities can benefit from the investments of higher-resource municipalities. And partially because the investments are going to be much more efficient and effective when not constrained by the artificial administrative boundaries of cities. So I think this new state legislation [SB 272], which requires every Bay Area municipality to have a sea level rise adaptation plan, is a really good approach. The BCDC has been trying to walk this interesting line between giving enough autonomy and flexibility to local municipalities to respond to their values and resources and also trying to create a bit of a framework to do coordination that everyone recognizes as necessary.

When are they going to arrive at the place where they start specific action plans?

SB 272 really just requires that plans get put in place. That is very different from investment and actually doing something. They're requiring municipalities to make a plan so that future investments are not done on an ad hoc basis according to whoever yells the loudest. But aside from that, there's adaptation happening all the time at different scales and levels, right? We have everything from individual property owners elevating their homes above the floodplain to things like the Foster City levy upgrades that happened a couple of years ago. It's happening all over the place, and it's going to pick up steam.

Climate adaptation will be a big part of what it means to be doing planning and urban design in this region, and really every region over the next several decades at least.

What role do wetlands play in this planning? Does sea-level rise pose an existential threat to marshlands in the Bay Area?

It definitely poses a real challenge. If not for urban development, the marshes would just shift inland in response to sea-level rise. They would gradually take over what is now dry land. Those species would move inland. But obviously, a lot of property owners are going to try to stop that process. If you allow a business-as-usual approach, individual property owners will build flood protections that stop the water from rising, which would also stop the in the landward migration of those tidal ecosystems. You get the squeeze effect, and the wetlands get drowned. We lose all of the incredible value that comes from wetlands, everything from flood attenuation to ecosystem and water quality benefits and biodiversity, and just the beauty of wetlands, which are magical spaces, right?

We are blessed in the Bay Area to have an institution like the BCDC, which tries to protect the wetlands. However, BCBC comes out of the 20th century environmental movement. At that time, there was tremendous destruction happening: dumping, filling, and industrial development in the bay. There was no appreciation for it as an environmental resource. The Save the Bay movement came and said, “you need to make a plan and protect the bay from landfilling and make sure that people have access to it.” It's really good that that happened.

The problem is that all these environmental institutions assume that the goal is to freeze the bay edge in place. With sea level rise, we’re seeing that we're actually not in charge. The bayshore is going to move inland. This reality calls for re-examining the BCDC’s mission. If we allow the bay to rise, let's figure out where there is potential for ecological preservation.

And on the other side of that equation, a complete prohibition against expanding urbanization of the bay itself is not the best solution because we know that in an era of climate change, we actually want to be encouraging higher density development in places that will allow people to live low-carbon lifestyles. And that means places that have access to jobs and transportation infrastructure. We think that there needs to be this kind of give-and-take approach to the bay shore that says, “let's identify the places where it can expand to provide the most benefits, and let's also identify those places where experimenting with new forms of urbanization will deliver the most environmental benefit and help us address our housing crisis.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.