What Will It Take To Get More of Us out of Our Cars?

Plus the latest on the Trump Administration's attacks on climate action in California.

Welcome to issue # 6 of State of Change, a monthly newsletter from the Climate Equity Reporting Project.

California Climate News

The Big Picture

The Trump Administration’s funding freeze is having wide-scale impacts across California, including the potential loss of more than $1 billion in federal EPA funding. The agency could backtrack on the 500 million grant that was awarded to the South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD) last summer to support the Inland Empire’s transition to electric trucks and trains in an effort to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions caused by the rapidly expanding shipping industry there.

A spokeswoman for AQMD told The Washington Post, “the grant has disappeared from the federal payment system and is ‘effectively frozen now.’” The state also received nearly $250 million from the federal Solar for All program, which is also frozen.

Aaron Cantu over at Capital and Main wrote: “There are only limited circumstances under which a federal agency can legally cancel an obligated award. The Trump administration could launch an audit of a recipient to search for any breach of contract to justify terminating the award, or simply claim the government’s priorities have changed, though those actions can be challenged in court. More simply, federal agencies can slow funds by decimating staffing responsible for delivering the award money or dragging out the reimbursement process.”

And given the Administration’s stated goal and initial moves to do away with the “endangerment finding”—or the rule that found in 2009 that greenhouse gas emissions “may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare”—in order to undo decades of work on climate by the EPA, it’s not looking terribly likely that those funds will ever “unfreeze.”

Meanwhile, federal agencies are hemorrhaging employees that work on climate, including nearly 400 from the EPA, at least 1,200 people from the Department of Energy, several thousand from the Department of Agriculture, 3,400 from the U.S. Forest Service. The National Science Foundation, which provides funding for research at universities around the nation, also fired 168 people on Tuesday.

And a federal judge dismissed the case brought by 18 young people in California against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for harming children’s health and welfare over decades. The judge stated that since all people will experience the harms associated with climate change, the California youth don’t have special standing to hold the federal agency accountable—i.e. their suffering is too “indirect” to matter.

Climate Impacts

Berkeley Earth reports that January 2025 was the warmest January since records began in 1850.

Mudslides are a serious risk in recently burned areas, and the recent rainstorm in Los Angeles brought a new danger to the area. A car was swept into the ocean and many roads were left covered in a thick layer of mud.

Phase two of wildfire cleanup has begun in Los Angeles. According to laist.com: “Debris that can be reused, including wood, metal and concrete, will be sent to recycling facilities. Ash will be sent directly to landfills. Six inches of topsoil will be removed in addition to ash in an effort to mitigate contamination.” However, the Army Corps of Engineers announced in a news conference that it will not order soil testing at properties damaged by fires. The LA Times reports that the shift “breaks with a long-standing safeguard to ensure no lingering contamination is left behind.”

Propublica took a deep dive into how the new administration’s federal funding and hiring freezes could leave more people vulnerable to catastrophic wildfires. According to the story, “the uncertainty has limited training and postponed work to reduce flammable vegetation in areas vulnerable to wildfire. It has also left some firefighters with little choice but to leave the force.”

Transportation

California’s clean truck mandate—the Advanced Clean Fleet Mandate—is looking dead in the water for now, after the state withdrew its request for a federal waiver that would have allowed it to move forward with the mandate. While the shift doesn’t bode well for the state’s carbon emissions or pollution goals in the short term, some experts have suggested that it might be a good time to rethink the state’s approach to electrifying the trucking industry. “A far simpler way forward is to restructure existing annual registration fees for trucks to reflect vehicles’ pollution impacts,” wrote EC Berkeley economist James Salee earlier this week.

New California Energy Commission data suggests that zero-emission vehicle sales in 2024 remained mostly unchanged compared to 2023, marking a shift from an increasing trend over the past several years. This, as well as the potential elimination of the $7,500 federal tax credit for zero-emission vehicles by the Trump administration, poses challenges for California in meeting its goal of 35% of new 2026 car models sold being zero emissions. According to CalMatters, affordability of electric vehicles remains a crucial barrier for consumers.

According to the SF Chronicle, San Franciscans are moving farther away from their job. There was a 5% increase in the percentage of workers living 50 or more miles from their jobs in 2022, compared to 2012. The data does not account for who is commuting or working from home, however, so the daily miles traveled per capita in the San Francisco metro area has gotten smaller. For some, the appeal of leaving the city is a more spacious home, however, and in that case heating and cooling can bring its own share of added carbon emissions.

In an interview with Forbes, General Motors President Mark Reuss said the company continues to see new customers coming in to buy electric vehicles. “That’s largely due to West Coast/California/high EV-adoption states giving us a chance,” said Reuss. But overall Californians aren’t buying the cars fast enough to meet the state’s climate goals. And despite the new administration’s vow to do away with the EV tax credit, Americans haven’t officially lost that option yet—even if changes to the IRS reporting system have made it next to impossible for some customers to claim their credits. Late last month, the California Transportation Commission announced a $1 billion investment in “projects aimed at solving mobility challenges and aiding California’s continued effort to make the highway system more resilient to climate change.” The funds will increase electric charging infrastructure for cars and buses, as well as increase and improve bike and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure across the state.

LA Times Climate Columnist Sammy Roth reported that the abandonment of the Pac-12 athletic conference by UCLA, UC Berkeley, and Stanford has had dire consequences for global warming. Athletes typically travel long distances by bus and plane, leading to a great deal of carbon emissions, and the shift has resulted in longer trips for more athletes. Between the 2023 and 2024 seasons, “UCLA had the biggest carbon footprint overall of any university football program, followed by Berkeley and Stanford,” wrote Roth.

Housing

As part of his budget proposal to the Legislature last month, Governor Newsom suggested the creation of a new California housing and homelessness agency. The proposed agency would help streamline the administrative structure for addressing the state’s housing and homelessness issues. “It’s safe to say this effort could be hugely important for Los Angeles County as it contemplates rebuilding,” wrote Ben Metcalf, managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, in an op-ed for the SF Chronicle.

Meanwhile, both Governor Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass have issued orders to reduce red tape and regulatory barriers that could slow rebuilding efforts in the city. This included the waive of environmental reviews and a suspension of a city requirement that mandates new construction to be all-electric. As a result, “many builders will default to gas furnaces and water heaters—instead of more efficient electric heat pumps that don’t use planet-warming fossil fuels,” wrote Los Angeles Times columnist Sammy Roth.

The Los Angeles wildfires prompted State Farm, California’s largest home insurer, to seek a 22% emergency rate increase for homeowners (alongside a 15% increase for renters and a 38% increase for condominium owners). On Friday, however, California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara denied State Farm’s request.

According to Newsweek, a recent study by First Street found that climate-related risks could erase $1.47 trillion in home values over the next 30 years.

The Energy Transition

Grist reports that California renewables fulfilled 100 percent of the state’s electricity demand for up to 10 hours on 98 of 116 days. This is a new record for clean energy in the state.

The massive fire at PBF refinery in Martinez injured six people and emitted a noxious combination of chemicals and combustion byproducts that are linked to cancer as well as heart and lung disease. And while the company will face a fine, the cost will be nowhere near as high as it might have been if the Polluters Pay Climate Cost Recovery Act had passed through the California legislation last year. Instead, Inside Climate News reported, PBF and other oil and gas companies spent tens of millions to lobby state lawmakers to prevent the bill from passing.

Decarbonization

Only one nuclear plant (Diablo Canyon) is operational in California and the state has had a moratorium on the construction of new plants for nearly 50 years. Now, largely due to concerns about the growing energy demand caused by AI data centers, some lawmakers may be considering the idea of building more plants. CalMatters reports that Microsoft, Google, and Meta have all signaled interest in nuclear energy in other states, and they are looking into an allegedly safer version of the technology called small modular reactors. The concerns—about the cost of waste disposal and the potential for reactor meltdowns, and other catastrophic events—that led to the moratorium haven’t gone away, however.

The state’s first neighborhood-scale decarbonization project at Cal State Monterey will no longer be moving forward, despite years of preparation on the part of the school and PG&E, the utility that would have helped fund the project. The goal had been to remove a gas line and electrify 400 homes. KQED reported on the likely decisionto terminate the project earlier this month and State of Change confirmed with both PG&E and the university that it will not be moving forward.

“The South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD)–which regulates air quality for 17 million residents in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties–is proposing new rules for replacing gas furnaces and water heaters in homes and buildings much like its Bay Area counterpart has done. A working group met on the issue last week.

A Little Good News

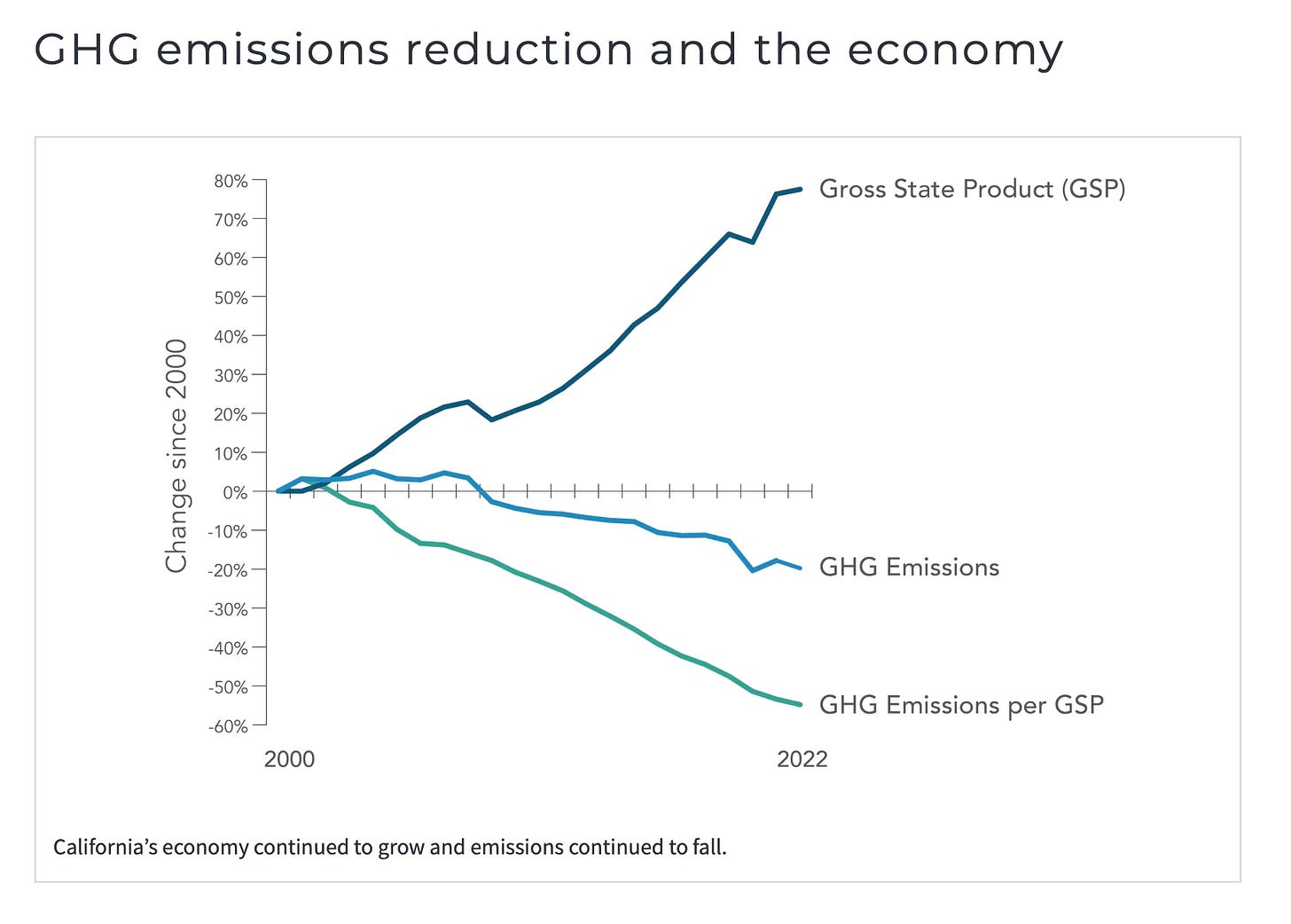

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) released a report showing that the state's emissions continue to fall—a 20 percent reduction between 2000 and 2022—at the same time that the California economy has grown substantially.

Q&A: Awoenam Mauna-Woanya Wants us to Drive Less

By Twilight Greenaway

Getting around in Los Angeles without a car isn’t an easy or popular choice, but it’s not impossible either. It just takes planning, patience, and steady sense of commitment, says Awoenam Mauna-Woanya.

The building decarbonization engineer at the California Air Resources Board (CARB) recently wrote about his efforts to avoid driving in the city with the most extensive freeway network in the U.S. “Choosing to live in Los Angeles, a city synonymous with car culture, without a car might seem impossible—borderline madness,” he wrote. “You always hear about the massive highways, the endless congestion, and its non-existent public transit system (not true!). So, when I tell people I don’t own a car, I get crazy stares of disbelief.”

Originally from Ghana, by way of Baltimore, Mauna-Woanya produces Fostering Our Earth, a podcast and newsletter focused on the intersection of urban planning and climate justice, where he argues eloquently for inclusive, safe public transportation as the cornerstone of urban mobility. He also spends his free time working with the Sunrise Movement LAand Urban Environment LA to improve housing and transit infrastructure in his community and inspire people to find alternatives to driving.

We spoke with Mauna-Woanya about the challenges of going (mostly) car-free, the charms of micromobility, the link between affordable housing and safe streets, and how to prevent bike lanes from spurring gentrification.

Tell us why you chose not to drive in LA and how it’s working out for you.

When coming to LA in the first place, I knew that I didn't want to own a car. I had done the calculations and realized that cars are expensive and dangerous. We're averaging around 40,000 car accident deaths per year in the U.S., and several times more people are injured every year. So I thought: If I can go as long as possible without having to own a car I'm going to try to do that. At the time I worked 2-3 days a week in an office in downtown Los Angeles and I still occasionally commute to a co-working space downtown. The decision to avoid owning a car really shaped my apartment hunt. I limited where I wanted to live to areas near LA Metro lines and bus lines so I could get downtown easily. That ruled out some fun neighborhoods like Silver Lake and Echo Park, but it’s worth it. I live in Pasadena, and there's a metro line here that runs straight to downtown, and then all the way down to Long Beach.

Choosing to live [right next to transport] is key to living as car-free as possible because the first and last miles are some of the biggest barriers for people. I chose to live a one-minute walk away from a bus stop and with Google Maps I'm able to see when the bus is coming, and I just step outside to catch it to the Metro. And I bought a scooter thinking to use that as my “last mile” connection, but I found that I also really liked walking.

When you use transit and walk around a lot you start to notice the shortcomings in the communities you live in, like the lack of proper non-car infrastructure. So often I would have to either be riding my scooter on roads, with cars driving by me, or I had to ride on sidewalks, which were very uneven and also pretty dangerous. And I started to think about folks who might have other mobility impairments—who are in wheelchairs or on crutches, or parents pushing strollers. The lack of bus shelters [can also be a problem]. It gets really hot in LA in the summer, and when you are all dressed up, going somewhere, and you're waiting 15 minutes for a bus and there isn't any shade or anywhere to sit, it can get pretty uncomfortable.

Buses and trains don't usually run as late as I would like, and that in itself can be a big shortcoming. After 10 or 11 at night, it can very quickly turn into a couple-hour journey home. My partner has a car, and if we know we’ll be coming back super late, or I need to go somewhere very early, I do have access to a car if I need to use it.

You mentioned a scooter. Micromobility is picking up steam as a strategy for reducing the amount of driving people do. Do you think it’s an effective strategy for cutting emissions?

I'm a big fan of micromobility options, and I think the key word is options. I think the biggest issue with how we designed our urban environment is that you really must drive and that in itself is pretty limiting. [We should all be] able to choose the best way to get somewhere for our needs. And so that might mean walking or biking, or tons of other options. Micromobility plays this beautiful role as a great last-mile connector, or an in-between-transit lines connector. And it can also be good for different kinds of people—whether you're a professional, or a younger person who needs to get around without a license and a car.

Electric bikes are also a form of micromobility. A lot of the discourse has been about how dangerous unregulated scooters and e-bikes are. Some cities have talked about making you get a license to be able to ride an e-bike around, or straight up banning scooters. And yet, cars are a million times more dangerous. And due to our lack of developing proper, dedicated bike and scooter lanes, people are forced to ride on the sidewalks. But I think if we built the infrastructure to support these mobility options, lots of people would find them to be better ways to get where they need to go. And in doing so, we would be taking people out of their cars, which will reduce congestion. So it requires a system-wide approach; we have to provide all of these options.

Do you have thoughts about the potential connection between investment in infrastructure for more active mobility and micromobility and the potential for gentrification?

I’ve heard stories about lower income, marginalized communities not wanting bike lanes because it could start to symbolize future gentrification, and I think that’s a problem of messaging—whether the people making the changes understand their community, how they’re pitching the changes, and who is doing the pitching.

People in some communities might not think that a bike lane is their biggest need. They might have a million other issues in their city, and that’s one reason efforts that are going toward building bike lanes and fixing the sidewalks might be met with resistance. People are afraid of displacement. But if we put better systems into place to [actively prevent it]—like a rent control measure that prevents an increase of more than 1% - 2% year over year—then even putting in a bike lane or a Starbucks won’t lead to displacement.

Do you have thoughts about the link between affordable housing and expanding access to more mobility options?

Those two things go hand in hand. We need to think [deeply about] what we're building, where we're building it, and why it's being built. If we build what’s called transit-oriented development and design our cities around transit, then people won’t have to worry about walking 20 minutes on either end of a trip to get to the store or to their dentist appointment.

And in order to develop housing around transit, we need to change land use requirements. There have long been parking minimums that say that if you're building, say, a grocery store, a restaurant, or a bar there's a minimum number of parking spaces for that property. But with better land use policies, and without these parking minimums we can design cities that are more walkable, less spread out. The other challenge is single-family zoning, which limits the kinds of housing you can build and the number of people you can house in most areas.

Without parking minimums and single-family zoning we can build apartment buildings that are basically right next grocery stores or dentists, and so now it makes a lot more sense to put a bus there, or to have a subway line go underneath that street, because you know that people will use that line, and people will be coming to this area to go to the dentist. And people who live there don't have to own a car.

That [kind of planning] can work well because—after rent—owning a car is the second largest expense for people in lower-income communities. And when we start to approach housing and mobility with a systemic approach we can imagine how we want our communities to look in 10 or 15 years and build toward those goals.

Are there inspiring anecdotes or examples you want to share of places where policymakers are rethinking or improving that connection between transit and housing?

Assembly Bill 2097—which put a stop to parking requirements in buildings located near transit—passed in 2022 and is a good example of that kind of work here in the state.In South Bend, Indiana the city has pre-approved a range of different multi-family home designs so that people can easily just choose an option and skip the whole permitting and development approval process. Cambridge, Massachusetts which just voted to eliminate single family zoning. And Austin, Texas has implemented a suite of measures such as allowing “missing middle” housing (duplexes, fourplexes, and other mid-sized development options) on single-family zoned lots, resulting in increasing affordable housing.

You mentioned in one of your posts that pedestrians are at an increasing risk and in particular pedestrians of color are at higher risk just walking down the street. How do we balance getting people out of their cars with making sure that they stay safe?

We can make driving safer by putting limits on how big cars can get. Cars have been getting larger and larger over the last few decades. We can also put speed limiters in cars to make sure cars don't go faster than 70 or 80 miles per hour, and really do whatever we can to minimize the human error that comes with driving a car.

And we can think about the roads themselves. We design these big, wide-open roads that are three or four lanes across and scream: Drive fast! They can also take a long time for people to cross and that's pretty dangerous. Especially when you have older folks or folks in wheelchairs. We can also add more daylighting laws to cut down on traffic accidents [by stopping parking near a crosswalk]. These design choices are really meant to minimize the risk rather than expecting everyone to be a good driver all the time.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.